In 1879 and 1880, freedmen (former slaves) from the South sent Kansas Governor John St. John around 1,000 letters seeking information on a possible migration to Kansas; a migration generally known as the Exoduster movement. Governor St. John responded to many of those letters. This epistolary exchange between Kansas’ highest official and the freed people of the South documents the hardships, hopes, and misconceptions of southern blacks at the end of Reconstruction. On a more mundane level, it provides insight into the letter writing customs at that time.

Most of the letters are seeking to corroborate rumors of free land in Kansas and incentives thought to encourage African American settlement in the state. Community and religious leaders penned many of the letters on behalf of larger groups of people, such as small communities or churches.

Though the envelopes of the letters have not survived, many were likely addressed to “John St. John” instead of the “Governor of Kansas.” Isaiah Montgomery  explains: “note that I address you without prefixing title in order that the letter may not attract undue attention. Nothing is too hard to suspicion of this Country where it has been the custom for a century or more to ransack the mails to prevent the circulation of documents breathing the spirit of freedom.”

explains: “note that I address you without prefixing title in order that the letter may not attract undue attention. Nothing is too hard to suspicion of this Country where it has been the custom for a century or more to ransack the mails to prevent the circulation of documents breathing the spirit of freedom.”

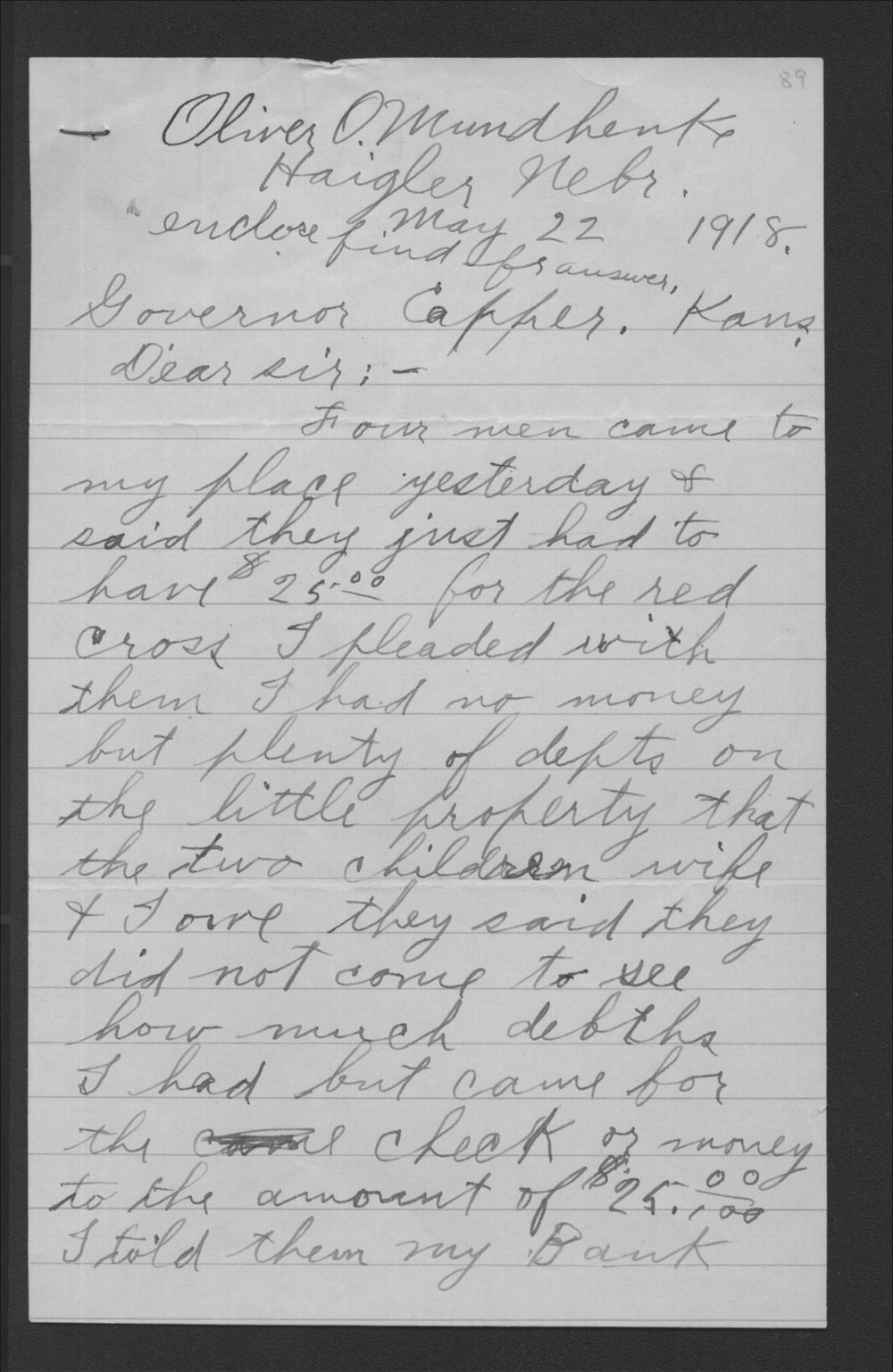

Upon receiving a letter, the Governor’s Office summarized its contents on a memo, noting the author’s name and date, and pasted the memo to the back of the letter. Staff filed the letters first by subject (i.e. “immigration – Negro exodus”) and then in chronological order. St. John or his secretary would then pen a response and “press” a copy of the reply into a letter press book. Pressing involved wetting copy paper (often referred to as “onion skin”) with water, interleaving letters between these wet leaves, and applying pressure to the whole until ink from the letters transferred to the copy paper. Too much or too little water could result in a poor copy.

Since many correspondents wrote the governor back after receiving his letters, it is obvious that many of the governor’s letters reached their intended audience. But did the governor intentionally conceal his title/office on the envelope as some of the letters request? Again Isaiah Montgomery: “Please address an answer (as early as convenient) with no mark on the Envelope to denote that it comes from the Capital or any official.”

Here at the State Archives & Library, we hold both the original letters sent to Governor St. John and copies of his responses “pressed” into letter press books. Some of the letters and responses are already available on Kansas Memory. We intend to add more of this correspondence to the site in the near future. See Governors for more information on our archives of Kansas governor's records.